Aidan became the target of systematic harassment from the British Army from the age of 17 years old. Although he was known by the British Army on sight, he would be held and questioned twice a day, every day, as he passed through the checkpoint on the British imposed border on his way to and from work in Monaghan. He was verbally abused daily and physically assaulted often.

His workmates recalled that Aidan could arrive at work at any time of the day, depending on how long he was kept at the checkpoint that morning. He would recount to friends at work how he would have been pulled out of the car by his heels, the car ripped apart and searched, and how British soldiers would urinate over the car and in his lunchbox.

His friend Mickey Muldoon, who was also experiencing relentless harassment by the Army and RUC, told how Aidan had to be prepared to be held for up to three or four hours any time he crossed the checkpoint or was stopped by the army. If he had arranged to meet Aidan at 8pm, he wouldn’t expect to see him till after 10pm. They would tear into the car, pulling out filters, so that Aidan would constantly have to repair the damage caused. They would go to the back of the car during the questioning procedure and disconnect wires and then penalise Aidan for not having brake lights or indicators.

One evening as Micky and Aidan were crossing through the Aughnacloy checkpoint, a Welsh soldier who was about a week into his first tour of the six counties, asked them how they put up with it. Even he couldn’t believe what they had to go through and said he couldn’t wait to get out of the north.

When Aidan was pulled over, the Brits would call over the radio that they had a ‘P1’. Mickey eventually found out that a ‘P1’ was code for a terrorist suspect, and that the Army were under orders to pull these suspects in, give them special attention and they could be arrested at any time.

Aidan was going out with Ita during the height of the harassment he endured. She said that on any given night, it was not a matter of whether or not they would be stopped, it was how many times. Ita knew not to get dressed up in skirts or high heels for a night out, as they would be guaranteed to spend hours standing at the side of the road or in the search shed at the checkpoint. The first night Aidan came to pick Ita up to head to the Glenavon Hotel, Cookstown he was so late that she thought she had been stood up.

It wasn’t long until the excitement and butterflies Ita felt after Aidan dropped her home turned to worry that he would get home safely. The harassment was so bad that when Aidan and Ita were standing at the side of road beside the car during a search, people who knew them would drive past without acknowledging them for fear of being associated with the couple and bringing the attention of the Brits onto themselves.

As the Brits got used to seeing Ita, they told her a few weeks before the Loughgall Ambush, “Your brother will be killed soon”, mistakenly thinking she was a sister of Declan Arthurs.

Ita has no doubt that there was a tracking device on Aidan’s car. It was too coincidental that they would be stopped on every road they travelled on, every time they went out. This happened on both sides of the border. On the way home from Monaghan one night, Aidan saw a car broke down on the side of the road, and, being Aidan, stopped to help. It turned out it was a priest who had run out of petrol, so Aidan took him back into Monaghan to get a jerry can. While the priest was in the shop, the Guards pulled up beside Aidan and began their routine of questioning and were just beginning to get nasty, but as soon as the priest appeared and told the Guards what Aidan had done and described him as a “good Samaritan”, they changed their tone, excused themselves and left.

Sister Margo remembers one evening Aidan came home from work particularly shaken and with tears in his eyes, with red marks on his neck after the Brits had had him by the throat. Aidan told Vincie that he had been taken into a black dark room and kicked and punched, not knowing what direction the next attack would come from.

His mother Liz would do her best to help and would travel to the checkpoint every day with him and walk home once he got through safely, and then walk down to meet him there every evening, as the abuse would not be as severe if she was present. She would have taken holy water out to bless his car every time he left the house. His father John could never settle while Aidan was out of the house. He would sit up to all hours waiting for Aidan to come home, and once he heard the car pull onto the drive, he would slip away to bed before Aidan come through the door.

Father Brendan McHugh came to Aughnacloy as the parish priest in 1982, when Aidan was seventeen. “He used to get a lot of harassment,” Fr. McHugh recalls, “and it went on and on and on. He came to me at times about the treatment he was getting, the language they were using, what they were threatening at times, because they did threaten, you see, that they would beat him up, that they would shoot him— I’m saying that they did threaten that many times, many times, now.”

At the end, he used to say, “I know, Father, you’re tired of listening to me telling you this,” and I would say, ‘Aidan, I know what you’re about before you start,’ and I would listen to him. I used to tell him to be quiet. ‘Answer their questions as far as you think they’re entitled to ask them, and just keep on going. And we’ll see who has the greatest courage—them or you.’

“It was my impression, and the impression of a great many others, that they wanted him to run. They would have loved for him to go off to County Monaghan and stay there, out of their way, so to speak. Then they’d have been satisfied. But he didn’t do that. He stayed going back and forth. I never expected it would end the way it did.”

After the death of the Loughgall martyrs in May 1987, it was a volatile time in the six counties, particularly around Tyrone, and the British Army felt they had the upper hand on the nationalist community in that area. This gave the Brits that bit more courage to goad and taunt those they knew to support the Republican movement.

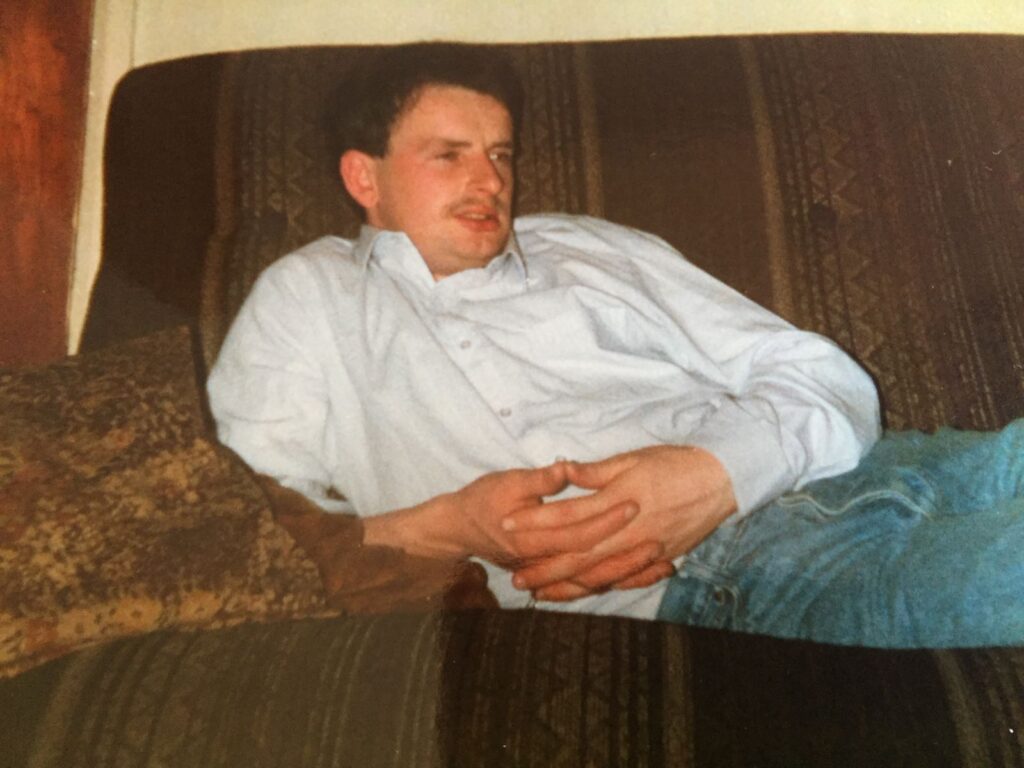

Around July 1987, Aidan was seriously considering moving across the border. He was becoming increasingly concerned about the threat the British Army posed to him, and was reaching breaking point with the horrific treatment he was constantly receiving. But he was torn between a relative freedom in the Free State, and staying at home with his parents. A ‘Sunday World’ newspaper article published shortly before Aidan’s death described him as “Ireland’s Most Harassed Man.“

In the weeks leading up to Aidan’s death, a British soldier pointed to his gun and told John, “We’ve got a bullet in here for your son”.